Can We Expect Vice President Biden to Convene a Hearing to Study the Influence of Novels on Real-World Violence?

On April 21 and 22, and June 4, 1954, the US Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held public hearings at which certain experts in juvenile crime were invited to testify along with artists and publishers of comic strips and comic books. Comic books as a medium did not fare well in the proceedings, as this Reductio ad Hitlerum testimony by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham suggests:

“It is my opinion,” Wertham told the senators and the cameras, “without any reasonable doubt and without any reservation, that comic books are an important contributing factor in many cases of juvenile delinquency.” The child most likely to be influenced by comic books, he said, is the normal child; morbid children are less affected, “because they are wrapped up in their own fantasies.” Comic books taught children racism and sadism—“Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic book industry,” he said. In his book, he said that “Batman” comics were homoerotic and that “Wonder Woman” was about sadomasochism. He was even critical of “Superman” comics: “They arouse in children fantasies of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while you yourself remain immune,” he testified. “We have called it the Superman complex.”

Note that the above quote, from a New Yorker review of The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America, says that Dr. Wertham was speaking to senators and cameras. That’s because these hearings, set up to discover the causes of the epidemic of juvenile delinquency, were televised. Today, of course, we’ve evolved beyond such nonsense. Today, when elected officials hold investigations into how the media is responsible for horrific crime, those hearings take place in secret.

Vice President Joe Biden said on Friday he was “shooting for Tuesday” to get President Barack Obama his recommendations on how to battle an epidemic of gun violence and warned “there’s no silver bullet” to stop the killing.

Biden was meeting in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building adjacent to the White House with executives from video game companies whose products have often been blamed for making players insensitive to real-world violence.

Just like the comic books of the 1950s, when Superman “arouse[d] in children fantasies of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while [readers remained] immune,” the video games of today have “often been blamed” for making players “insensitive to real-world violence.” And the federal government is on the case.

On December 19, the governor of Montana, Brian Schweitzer, was explicit in naming what he considers to be the cause of real-world violence:

“You wanna pick on somebody? How about those video game manufacturers, where an entire generation are glued to a screen for six to eight hours a day while they are poking buttons and blowing other people up and shooting them in the face.”

Jamie Foxx, the star of the current film “Django Unchained,” has suggested that film depictions of violence have some influence on real-world violence:

“We cannot turn our back and say that violence in films or anything that we do doesn’t have a sort of influence,” Foxx said in an interview on Saturday. “It does.”

This tendency among humans to “blame the media” for social ills and shocking acts of unpredictable violence is an unfortunate and ever-present part of human nature. It goes back a lot further than the 1950s senate hearings on juvenile delinquency. Here is an excerpt from an essay written by a poet and playwright called William Whitehead:

The thing I chiefly find fault with is their extreme indecency. There are certain vices which the vulgar call Fun, and the people of fashion Gallantry; but the middle rank, and those of the gentry who continue to go to church, still stigmatize them by the opporob[r]ious names of fornication and adultery. These are confessed to be in some measure detrimental to society, even by those who practice them the most; at least, they are allowed to be so in all but themselves. This being the case, why should our novel-writers take so much pains to spread the enormities? It is not enough to say in excuse that they write nonsense upon these subjects as well as others; for nonsense itself is dangerous here. The most absurd ballads in the streets, without the least glimmering of meaning, recommend themselves every day both to the great and small vulgar only by obscene expressions. Here, therefore, Mr. Fitz-Adam, you should interpose your authority, and forbid your readers (whom I suppose to be all persons who can read) even to attempt to open any novel, or romance, unlicensed by you…*

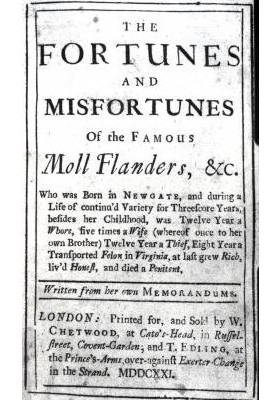

Mr. Whitehead wrote these words in 1753, in regards to a relatively new literary genre, the novel. Thanks to advances in printing technology, it wasn’t just the upper classes — who presumably could handle the scandalous subject matter depicted in literary works — who had access to printed material. Novels often depicted behavior that Mr. Whitehead, and other high-minded individuals, considered to be indecent. (Daniel Defoe alone had written at least two novels with sympathetic depictions of prostitutes in the early 1720s!) These depictions of indecency might in turn influence other, low-minded individuals, to behave indecently. Merely depicting certain vices would cause the spread of those vices. In other words, the novel might lead to an entire generation glued to pages of words for six or eight hours a day, learning about vulgarity and iniquity. The novel might make readers insensitive to real-world violence. The novel might arouse in readers fantasies of sadistic joy in seeing people punished over and over again.

On December 14, 2012, a disturbed man in Connecticut murdered 27 people, including 20 children, and his own mother. The event was shocking for its brutality and its senselessness. Since that day, people have struggled to find a way to prevent such unpredictable acts of violence from ever happening again. They’ve attempted to assign blame beyond the person responsible. The soul-searching that’s been going on recently in the media is nothing new. Human beings have been doing it for centuries, and they will apparently continue to do so, even as real-world violence continues to decrease.

*Essay collected in Novel Definitions: An Anthology of Commentary on the Novel, 1688-1815, edited by Cheryl Nixon.

S#!T Talking Central